Evacuees

When war broke out in September 1939, the greatest fear of many people was the bombing of cities by the German air force (Luftwaffe). This stemmed form the fact that aeroplanes had developed greatly during the 1920s and 1930s and it was widely feared that aerial bombing would the main feature of future wars.

In particular, people looked to the example of Guernica in Spain, which had been bombed in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War. It was feared that a similar fate would come to the people of British cities. As a result, in the first four days of September 1939, nearly three million people left cities and towns to find safer places in the countryside.

Some evacuees soon went back when aerial bombing did not begin immediately, but many stayed away for much of the war, and others left cities later. As a small rural town, Hemel Hempstead was a destination for many evacuees. This section includes stories of people who were evacuated to the town from London, but also of local people who were sent away to deeper countryside.

Audrey Mullard's story

(Interviewed by Sophie Horwood, November 2008.)

Audrey Mullard was Audrey Deller when war broke out, and a four year old old resident of Tottenham in north London. She was evacuated towards the end of 1940 and remembers how she left London with her mother and sister. She was very unhappy to leave her father working in London, along with her cat. The family was moved around different places. Audrey says,

We were billeted with four different families in Hemel Hempstead. We were assigned a billeting officer who had previously gone round to houses in the area. If householders had one or two spare rooms they were obliged to take in refugees. The host families were paid a small fee for each evacuee they took in.

It was not easy being with another family. Audrey says:

Although we got on reasonably well with one family that we were billeted with, unfortunately I have no happy memories of the others. In one billet we would leave a roaring fire and have be in our cold bedroom before the man of the house came home between 5 and 6 pm. We had a sparsely furnished bedroom with a lino covered floor, and there was just one double bed for my mother, sister and I. We would stay huddled together throwing coats over us for extra warmth. Mum said she would sometimes walk us round the streets so we did not get back to the unhappy billets too soon. We always had to be very quiet whilst in these billets.

Despite these bad experiences, Audrey says:

I suppose it is understandable that host families did not particularly want a mother and two small children staying with them. Then again, we did not want to be there either but we did not have much choice in the matter.

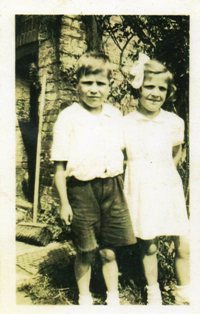

Audrey pictured on the left next to her sister Shirley and in front of her mother.

Note the gas mask cases.

Read more about Audrey Mullard's life as an evacuee in Hemel here.

Hazel Wilkinson's Story

(Interview by Sarah Kay and Amelia Wright, February 2009.)

Evacuation

Hazel Wilkinson lived with her two sisters, Mary and Janet, in Hemel Hempstead with their parents before the war began. Her father knew that war was imminent and their parents decided to evacuate them privately. Hazel’s parents had spent their honeymoon on a farm in Wales and they sent the children there. Hazel recalls, “Our mother took us to Wales as by this time my father was in the army. We went through London which was being heavily bombed at the time and I remember the red sky from the previous night’s raids. It must have been very frightening for our mother.”

Farm life

Life on the farm was very different to that in Hemel, but the routine did not vary much. Hazel said, “Mondays were market days when Mr and Mrs Jones dressed in special clothes and went to market in a pony and trap, taking things like eggs and mushrooms. There might be a pig in the back of the trap. If it was not a school day one of us was allowed to go. That was a real treat. Baking was done in the bake house at the back of the scullery. A fire was lit in the oven and when it was really hot the bread for the week went in followed by cakes and pastries. That was the day we had our bath as the bake house would be warm. The bath was a tin one that usually hung on the wall of the scullery. There was no electricity or gas.”

An advantage of being on a farm was that fresh produce was close at hand. Hazel recalls: “Local people got their butter and cheese rations from the farm. We think we had more than people who lived in towns.”

School

School was also very different to the one Hazel attended in Hemel: George Street Primary School: “It was a 3 class village school. The head teacher taught my class. He was a gifted musician but certainly not a disciplinarian and chaos reined for much of the time. Mary was in the next class with a female teacher who was also a good singer and Janet was in the baby class. Every morning assembly went on for ages as Mr R played the piano, Miss P sang and we had lots of hymns. The age range in the top class was from 9 to 14. The bigger children, especially the boys, were allowed time off to help on the local farms. Lessons were haphazard. We had time off to collect sticks for wood for the school boiler.”

Mixed emotions

Life on the farm was idyllic in many ways and gave the 3 sisters a unique experience and many memories, some good and some less happy. Hazel remembers, “We did see our parents occasionally when my father had some leave. I knew that they had arrived because I could smell my mother’s perfume as she came up the stairs to our bedroom. When they came we often went to the local town (Welshpool) and the river Severn where our father fished and cooked the fish for lunch. They were happy memories.”

Despite these happy memories, Hazel says that she “was mostly very unhappy, apart from missing my parents and our settled life at home. I was a ‘square peg in a round hole’. I was a real bookworm and when our parents sent us a parcel it often contained a book for me. I instantly wanted to read it, but was discouraged by Mrs Jones. I also know now that I spoke out of turn. One time when I should have shut up was after a parcel arrived from our parents. They sometimes sent us sweets as our father would swap his tobacco allowance for sweet coupons. Mrs Jones would let us choose one item then put the parcel away, but she would bring it out when relations called and give them lots of sweets. I would say that they were ours. Not a good idea! When we did finally leave the farm 15 months later I was an extremely nervous and unhappy person. My sisters were not so affected as Mary loved life on the farm and Janet, although she was very young, was fortunate to be little and arouse the motherly instinct amongst those on the farm.”

Hazel and her sisters enjoy a day out by the river near to the farm where they were evacuated in 1939.

Read more about Hazel Wilkinson here.

Jean Kelley’s story

(Interview by Sarah Jane Kay, August 2010.)

This is the story of Jeanette (Jean) Anne Martin, her twin brother James (Jimmy) Vernon Martin and older brother Ernest Peter Joseph Martin, who was always called Peter. They lived in Malden Road, Kentish Town in London.

We were evacuated on 3rd September 1939 from Fleet Road School in Hampstead, London. We arrived in Berkhamsted (Hertfordshire) with nowhere very much to go. Children were lined up and delegated to various people who said things like, “I’ll take this one and I’ll take that one”. We were pretty much the last on the list as twins and an older brother who didn’t want to be separated and we kept holding hands. It was getting dark so they took us to a temporary billet in a very affluent house but we couldn’t stay there for more than a couple of days. The lady there was quite unkind despite the fact that we were very young. Jimmy and I were barely 6 years old and Peter was 10. There was some talk of people taking us in during the day time and sending us somewhere else to sleep but that didn’t work out. Peter was a very endearing boy with blond hair and a mischievous way and he was eventually chosen. No one really wanted to take us twins until Aunty Lizzie said she would have us.

The people who took Peter were very cruel and treated him badly, for example locking him in a cupboard under the stairs. My Mum would give him half a crown, a lot of money in those days, to buy lemonade and a biscuit when the family went out. But they would get him a glass of water and no biscuit and take the money. He was so unhappy he ran away and hitch-hiked and walked back to London, about 28 miles….

Because he had run away Peter was tarnished and was sent back and put in a strict boys’ camp run by the Boys’ Brigade in Great Gaddesden. [The camp was probably the one at St Margaret's close to Great Gaddesden, details of which are here.] But this wasn’t fair because he had run away because of the cruelty. The children there lived in big black huts. I’m not absolutely sure about this but I think he could not leave until he was old enough to work. But anyway, he had to stay until he was about 14 years old….

Uncle Charlie and Aunty Lizzie Holiday were already old when they took us in. Aunty was in her seventies at the end of the war. She dressed very Victorian-like with her hair in a ‘cottage loaf’ bun. Uncle Charlie had been gassed in the First World War and was a semi-invalid. Aunty had been a nurse. They both worked at Berkhamsted Girls School where he was the caretaker and she was the matron. We picked apples that grew in the school grounds and wrapped them in blankets and stored them in the cellar. We also stored nuts in sand in tins. They were not to be eaten until Christmas. We ate well. It must have been quite costly to take on 2 children when they had none of their own….

We were called names by the local children such as Londonite and guttersnipe. You were only allowed to take one little suitcase, not much bigger than the gas mask case, with a change of underware. We weren’t dressed smartly so we were called names. We spoke slightly differently to the rural language of the time and the accent at that time in Berkhamsted was very strong. Aunty Lizzie got hold of some clothing for us and Mum made me a few dresses and sent them, but Jimmy played out in the garden in threadbare trousers to save his only decent pair.

We were shielded from the full harshness of what was happening in the war but we could listen to the *wireless and at night-times you could sometimes see ‘dog fights’ between English and German planes and we saw some planes come down in flames. But this was small compared to what was happening in London. You could hear the barrage in London. You also knew that because of what was happening you might not see your Mum and Dad again. They were living in danger all the time.

*Wireless - radio

Jimmy and Jean Martin

Read more about Jean Kelley here.

Daisy Lowe's story

(Information sent by individual, July 2009.)

Daisy Lowe was born Daisy Brannon and was living in Islington at the start of the war, when she was seven years old. She was evacuated with her six year old sister, June, her baby brother Terry, her mother, and other relatives.

On the journey from Euston to somewhere in the midlands, we were puzzled when the train stopped at Hemel Hempstead & Boxmoor station at about 11 a.m. WAR HAD BEEN DECLARED. All transport was immediately halted in England and we had to get off and lie down under the horse-chestnut trees on the moor by the Fishery Inn. A beautiful spot…. Later we had to take what seemed a long walk to St. John's Hall where the W.V.S. (Women's Voluntary Service) had tea, orange juice and biscuits organised for us. The good ladies gathered to choose who they would accept as evacuees to live with them. My mother had to choose the two younger children to go with her to Mrs. Smith in Sebright Road, I was left out!

My aunt, Vi Davy, took me, together with her son Ron, to live in Grosvenor Terrace, and my aunt Lil and her daughter Maureen went to Horsecroft Road. After a very short period of time Mrs Smith agreed for me to join my family and before my father was called up into the Royal Artillery he also spent weekends with us. We attended Cowper Road Infants School and later St. John's School with Mr W.G.S. Crook as headmaster. We used to ride our roller skates to St John's School but a policeman stopped us because the skates made a sound like something dropped by German aeroplanes….

At the age of 11 years I was not allowed to sit the examination for the Grammar School because I was an evacuee, even though I had attended local schools for 4-plus years. Mr Crook was incensed at the discrimination and arranged for me to sit the London Board examination. As I passed this examination he again put me forward for the Grammar School but by then I had to spend a year at Corner Hall School ….

Whilst at Corner Hall School we were taken swimming and one day a teacher was vigorously demonstrating what to do when she fell into the pool! Lots of cheering from us but Mr Whittle, the pool superintendent, restored order. At Corner Hall I spent many hours in the shelters during air raids when we were all encouraged to sing and were given barley sugar sweets.

Read more about Daisy Lowe here.

John Stanbridge's story

(Interview by Lynda Abbott and Fay Breed, November 2011.)

John Stanbridge's farm, St Agnell's, hosted evacuees during the war. He remembers:

We had a Welsh school teacher billeted on us and we became lifelong friends. We had two school teachers. One (the Welsh lady) did everything she possibly could to help – did the washing up, made the beds ready… The other thought she was in a paying hotel and did absolutely nothing. You can know which one we liked! The one we didn’t like left after about 18 months. The other one actually got married from the farm in the local registry office. They hadn’t really got any family left of their own. My parents were like grandma and granddad to them. We called them our Welsh branch.

A funny thing happened to her in the war. She did advanced Welsh at Bangor University. One day the South Wales Borderers were on the little village green on manoeuvres (in Cupid Green). As she cycled to school one of these men passed some very spicy remarks about this young lady. She had enough courage to keep on cycling straight up to them and speak to them in their own language. They didn’t expect in a little country village in Hertfordshire to find a perfect Welsh speaking girl.

Read more from John Stanbridge on evacuees here.